Eric “Guy” Earle

Parents – Arthur Moses & Effie

“Children” Guy Fred, Judi, Eric Davis, Anne, Philip, Elizabeth, Dennis, Guy. (two names withheld)

Sisters & Brother – Nell, Gert, Jean, Guen & Fred

Guy was married twice, First time to Mildred Davis and than to Elizabeth “Bette” Dawe. Guy Died of a massive coronary just a day before his divorce from Bette Dawe to Marry Carola Fletcher. In his Will Guy left most to his assets to his brother Fred for the business’s to continue running an undisclosed amount to his Wife Elizabeth and for her to collect his Social Security for the rest of her life and $3500.00 to his Daughter Elizabeth Patricia.

——————————————-

Eric Davis

Mother – Mildred Davis Earle

Children – Mark , Simon, Steve

Wife –

Born – Carbonear

Located to: Chalk Rive

Marks children – William, Christopher

Sylvia Judith “Judi”

Mother – Mildred Davis Earle

Children- Samantha & Stephanie

Born – Carbonear

Husband – Maxwell Haines

Located to: Ottawa

——————————————

Enid Anne

Deceased

Mother – Mildred Davis Earle

Children – Carmen

Grandchildren – Leanne Wilson, Callie, Jeffery

Leanne Wilson’s children – Bryce, Alex (Anne’s Great grandchildren)

Born – Carbonear

Located to: Ottawa

——————————————

Guy Fred

Deceased

Mother – Mildred Davis Earle

Children – None

Wife- None

Born – Carbonear

——————————————

Philip

Mother – Mildred Davis Earle

Children – Daughter Sara, Son – unknown

Wife – un-known

Born – Carbonear

——————————————-

Elizabeth ( Libby )

Mother – Elizabeth Dawe Earle

Children – Stepson – Zak DePiero

Husband – Brian DePiero

Born – St John’s

Location now – West Haven Connecticut USA

——————————————-

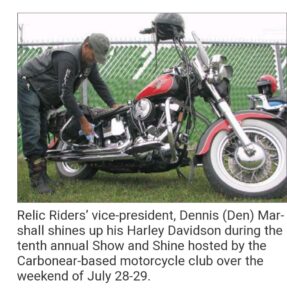

Dennis Marshall

Mother –

Children – Taylor & Casey

Wife – Louise

Born – Carbonear

——————————————-

Guy jr

Mother – Carola Fletcher – Manchester

Children – Eric William

Wife – Andrea

Grandson – Eric

Nova Scotia

Born – England,

Dolores Lawrence

Born – Freshwater

Born Jan 22, 1959

Married

Husband Thomas

Children Mitchell & Lindsay

Lives in Fort McMurray Alberta

Guys Sisters/Brother

Nell Josephine Earle – Mrs. Jack Anderson

St John’s

Born – July 17, 1912

Children –

Gertrude “Gert” Joyce Earle – Mrs. J King

Corner Brook

Born – September 18, 1914

Children – Elizabeth King

Sister

Frances “Jean” Earle – Mrs. Kennedy

Burlington Ont.

Born – May 1, 1920

Children – Gordon, Joanne & Susan

-‐————————————–

Sister

Gwendolyn “Gwen” Earle- Mrs. Brokenshire

St John’s

Born – Feb 1922

Children – Fred, Earlier, Howie, Jim

Frederick “Fred” Giles Earle

Carbonear

Born – Dec 30, 1929

Died Dec 30th 1999

Children – Mark , Simon, Steve

——————————————-

Dr. Davis Earle – History

Born in Carbonear, Newfoundland, Dr. Davis Earle followed his undergraduate degree at Memorial University (B.Sc., 1958) with a M.Sc. at the University of British Columbia in 1960. In 1959, he was awarded the Rhodes Scholarship and completed his D.Phil. at Oxford in 1964. From there, he moved to Chalk River Laboratories of Atomic Energy of Canada and began a long career of contribution to experimental nuclear physics.

His career took a different turn in 1984 when he joined a group of fellow scientists planning what would become the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO). The intent was to measure solar neutrinos using heavy water. This required an initial feasibility study and, once feasibility had been established, the development of a major funding proposal. Dr. Earle was a key figure in both these aspects of the project so that, when funding came in 1990, he became the project’s associate director.

He then undertook responsibility for construction of what was the equivalent of a 10-story subterranean building and of ensuring that the structure was ultra-clean – that the radioactivity was reduced to levels until then unachieved. The same demands were made of the massive acrylic sphere which had to hold $300-million of heavy water and is the crucial aspect of neutrino detection. Those demands were met and SNO’s work proceeded to receive international regard; to be viewed as among the most significant recent scientific discoveries and contributing to a better understanding of the universe.

Dr. Earle is also noted for his capacity to communicate scientific findings and has long been viewed by his colleagues as a scientific ambassador to the wider community.

For his major contribution to the initiation and development of SNO and to the standing of Canadian science, Dr. Earle will be awarded an honorary doctor of science degree at the 3 p.m. session of convocation on Friday, Oct. 22.

——————————————————————————–

DAVIS EARLE HISTORY –

www.sno.phy.queensu.ca/

Canada’s Health Minister Tony Clement speaks during a news conference at the Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. (AECL) Chalk River nuclear facility in Chalk River, Ont.

Photo by Chris Wattie / Reuters

Isotope hope

Nuclear physicist from Carbonear bemoans politics, flaws at Chalk River plant

By BRIAN CALLAHAN

Friday, January 18, 2008

For 44 years, Davis Earle has lived next door to the Chalk River nuclear power plant in Ontario.

And for 32 years, he worked there.

Clearly, the 70-year-old retired nuclear physicist from Carbonear feels safe in his adopted home, but he says serious issues continue to surround the important facility near his home in Deep River near Ottawa. Important for several reasons, but mainly as a source of two-thirds of the world demand for medical isotopes. Almost overnight, Chalk River went from relative obscurity to a household name when its importance as a supplier to hospitals worldwide was realized.

In late November, a nearly month-long shutdown due to safety concerns left hospitals from Newfoundland to New Zealand scrambling to find an alternate source of isotopes, which are needed to perform critical medical tests and procedures.

Earle, a Rhodes Scholar, says Chalk River operator Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. (AECL) recognized the potential crisis years ago and has been trying to replace and upgrade the reactor ever since.

In fact, smaller replacement reactors solely to produce isotopes — known as Maple 1 and Maple 2 — have been built adjacent to the 50-year-old reactor, but have yet to power up. Their startup is eight years behind schedule mainly due to design flaws and lack of funding from the federal government .“They’ve had problems with its design and can’t get it up to speed,” Earle tells The Independent from Fernie, B.C., where the avid skier vacations with his wife. “They’ve got them built, but the regulatory body won’t allow them to operate because of commissioning problems.”Earle, who worked at Chalk River from 1964-96, says a lead physicist at the facility told him last week there are still problems with the new reactors.“They still don’t know when they’ll get them running. It’s eight years behind now and the budget has gone through the roof. So that’s very embarrassing for AECL, that they haven’t succeeded in getting these up and running,” says Earle, who moved to St. John’s from Carbonear at the age of 13, and graduated from Prince of Wales College and later Memorial University with a bachelor of science degree.

He attended the University of British Columbia before enrolling at Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar. Earle then moved to Deep River to begin work at the nearby reactor. “There’s no question about it — AECL has got to have egg on its face because here they are … it was years ago they realized they had to come up with new reactors to produce the isotopes, they got money to build them, they got them designed, and they’ve been built. But they’re not working according to design.”

The regulator — Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) — ordered the shutdown in November, sparking a spat between federal Natural Resources Minister Gary Lunn and CNSC president Linda Keen.

Lunn criticized Keen for the closing, while Keen and opposition MPs fired back with accusations of government interference with an independent commission. While he sympathizes with Keen, who was fired by Lunn Jan. 16, Earle also questions the reasoning behind the shutdown. “I have to sympathize with her. She was in charge of the regulatory body, but if she’s suddenly looking over her shoulder to see if some politician is going to second guess her decision on a safety issue, and fire her if she doesn’t make the right one … I got a little bit of a problem with the government taking that position, even though she may have been a little too tight (with the regulations).”

Earle doesn’t believe Keen was the only casualty in the dispute. He says “other heads have already rolled” with some staff “moved laterally” into advisory roles. He also says the shutdown may not have been entirely necessary, but it was an opportunity for Keen, the CNSC and AECL to “draw a line in the sand.” “I think as far as AECL was concerned, this reactor was fine. It was just a question that they should have had certain battery backups in place, and they didn’t. So I think Keen decided the regulator was going to take a stand (to draw attention to the issue). And it worked.

“Maybe it wasn’t the most serious issue, but AECL had not done something they agreed to do. So either accidentally or intentionally they misled the regulator.” Earle also points out the Chalk River reactor reached its life expectancy years ago. But that, he says, still doesn’t mean there’s a safety risk. “It certainly wasn’t designed to last this long. It’s only because they’ve upgraded it, repaired and replaced things, they can’t get these (new reactors) working — and they haven’t been able to get funding for another research reactor — that it’s still operating.”

—————————————————————————————————————————

The first hour of the trip, crossing Conception Bay, from Carbonear to Cape St Francis was very peaceful. I remember it as a sunny, calm summer’s day and can remember saying to a crewmember as we rounded Cape St. Francis, “If the trip is going to be as smooth as this I will really enjoy it.” No sooner had I expressed this sentiment than we encountered the swells of the open Atlantic just north of St. John’s. The ship rose up twenty feet and crashed down. It repeated this process, ad nausea, and so did I. Within 15 minutes I lost my lunch and within two hours, as we continued south pass Cape Spear, I was reduced to heaving up stomach bile, green and foul tasting. Basically, I was reduced to lying in my bunk for two days retching bile every hour. Occasionally, my father managed to get me to down some water and crackers only to have them return ten minutes later. I remained in this condition for about two days. I can remember suffering through two nights.

My father repeatedly tried to get me out of the bunk but to no avail until, near St. Pierre, he call out to me from the wheel house that we were sailing through a pod of whales. I ignored him, thinking it to be a scam, and stayed where I was, in my bunk, until I heard a whale exhaling. I dragged myself out onto the deck and saw that he was telling the truth. By the time they were out of site I had been up long enough focusing on the horizon, which was stable and consistent with my inner ear, rather then being tossed around like the rest of me, that I was no longer sea sick. I was fine for the rest of the trip

We arrived in Halifax. It was the first time I had been further than the Avalon Peninsula. I had fun walking round the Halifax docks, checking out the shops and marveling at the stuff for sale, particularly the fresh produce. I zeroed in on bananas, one of the fruits I had never seen before. I bought a bunch, maybe a dozen or so, ate a couple and stored the remained near my bunk for latter treats. I horded them for too long, they turned brown and I panicked, eating as many as I could in one sitting. You will appreciate that they didn’t stay down for very long and resurfaced shortly after being consumed. In spite of this encounter my love for this fruit has stayed with me over the intervening 60 years and no day is complete without at least one.

AECL has estimated it will cost $600 million over the next five years to replace or improve the facility. But Auditor General Sheila Fraser, in her report last fall, said Ottawa has provided only $34 million to the Crown corporation to address “urgent health, safety, security, and environmental issues” at Chalk River. A source of funding for other significant costs has not yet been identified, she added. “When it was built, it was very safe,” Earle says. “But they’ve had to upgrade it to make it safer and safer as years go by, which is perfectly reasonably, just as cars didn’t used to have air bags or seatbelts.” Another result of the Chalk River crisis was a global realization of the scarcity of medical isotopes. The U.S., Earle says, is already considering modifying a reactor in Missouri to produce them. “You can appreciate that the Americans are saying, ‘What? We’re depending on a foreign reactor for that? We’ve got to have our own supply.’” Earle estimates about 2,000 people work in some capacity at Chalk River, which also serves as a testing and trouble-shooting facility for new reactors.

A close encounter with a cod jigger. My father was a seafaring man. With just a grade 8 education, he got his captain’s ticket at the age of 18 and sailed the east coast of North America and to Europe many times carrying freight for various clients. His exploits were many and are well known in Newfoundland folklore but few have been recorded. An exception is “Voyage Down to Labrador” written by William A. Ogletree fifty years after the event and posted on the Internet.

In the summer of 1949, at the age of 31, he and his 106’ long boat, the “Thomas S Gorton” (very similar to the Bluenose but with the sails replaced by a diesel engine and with a wheel house) was hired to load drums of airplane fuel in Halifax and bring them north to Frobisher Bay, now called Iqaluit, the site of a US air force base. I was eleven at the time and he invited me to join him for my first ocean going voyage.

From Halifax we crossed the mouth of the St Lawrence and entered the Strait of Belle Isle. Here we encountered the worst thunder and lightening storm I had ever been in. Being on a boat in the open sea with no obstacles to block ones view and it being dark probably made it seem more intense. We were loaded with drums of high-octane fuel, in the hold and on deck, so that in order to walk fore to aft we had to walk on oil drums rather than deck planks. My father became very agitated and concerned during this storm. If it hadn’t been for the lighting rod attached to the mast you wouldn’t be reading my account of this trip and the most interesting experience of the trip would never have happened.

My single recollection of the Labrador coast is how impressive the Torngat Mountains are from a few miles out to sea. This mountain range has many of the highest peaks, over 5000’, in eastern North America. But from the sea, it is the cliffs, some of which extend 2000’ straight out of the water which are awe inspiring. From my experience only the canyons of the Nahanni River can compete.Leaving Cape Chidley behind we crossed to Baffin Island and entered Frobisher Bay. Here we encountered sea ice and ice bergs. On one fine day I counted thirty icebergs surrounding us.

I particularly remember one of the bigger ones because of its uniform geometric shape. It looked much like a large football stadium. Frequently, we had to send a man up the rigging into the crow’s nest to look for leads through the drifting pack ice that blocked our way. My father insisted that I needed to experience the crow’s nest. You can tell from his photo of a little boy half way up the rigging that I was scared doing this. In fact, my current fear of heights probably was due to this traumatic experience.

——————————-

In the bay we also encountered two polar bears swimming in the water. My father shot both of them, winched them on board and had their pelts removed. I let him go once he cried uncle.

These pelts survived for many years in Carbonear but were eventually discarded. Probably because they weren’t properly cured. In both cases his shot entered the bear’s scull just behind the ear and that from a distance of at least 200’. His skill with a rifle was another of his exception talents.

In addition to my father the crew consisted of a cook, an engineer and four deck hands who shared the shift work, four hours on and four hours off except for the two two-hour dogwatches between 4 pm and 8 pm. One of the deck hands had an unusual affliction. When he was goosed from behind i.e. grabbed by the buttocks, he would jump, yell and hit whatever was in front of him with his hands. This could be a table, the wheel or a person. If taken by surprise while talking to my father he would strike out at him, resulting in a faked show of indignation from my father and a few blows as well. Eventually, we arrived at the community of Frobisher Bay. There was no wharf because the head of the bay is very shallow and has significant tides. We anchored several miles out from the high water mark and off loaded the drums onto barges for transportation to shore. These barges would approach the shore when the tide was in, become grounded and be unloaded when the tide was out. I didn’t see any of this because I was hospitalized the day after we arrived.

Early that first morning I was at the stern of the boat trying to hit a piece of kelp being carried out to sea by the tide. I was using a cod jigger, a nice solid weight. In order to make a second attempt before the kelp got away, I rapidly pulled in the line attached to the jigger. One of the hooks got caught in the wooden trim on the outside of the hull causing the line to become taunt and, the hook, acting like a spring threw the entire jigger into the air, over my head, past my shoulder into the back of my right hand. About 3” of hook, including the barb ended up in my hand. It entered near the knuckle at the base of my index finger and curved around about 90 degrees. The tip and barb ended up 0.5” down by index finger, below the surface.

Photo of a single hook cod jigger. My double hook jigger weighted in at about 21 ozs. The “meat” is a lead weight.

My scream alerted my father who was on a toilet near by and I can still clearly see him exiting the latrine with his pants still down around his knees. First he attempted to remove the jigger by pulling it back. That was completely useless, of course, and only produced a very negative reaction from me. The heavy weight of the “meat” of the jigger only exaggerated my discomfort.

He launched a small skiff and lowered me into it. We motored out to a large cargo ship anchored further out and he attempted to communicate with its crew about if they had a doctor on board. Either they didn’t or he was frustrated trying to communicate in a language other that English (probably the former). We turned around and headed for shore. The tide was out but a large army truck had traveled across the bolder strewn shore to the water’s edge to pick us up and take us to the base medical centre. The ride across the beach was the most painful part of the whole experience. I had recovered from the initial shock and the bumpy ride in the back of the truck was extremely uncomfortable. My father held me in his lap and tried to hold my hand and the jigger as one unit. He may have had some success in this endeavour but I wasn’t aware of it.

At the medical centre we met the man in charge. I don’t think he was a doctor but he was the medical boss. Recalling his behavior, I think he was a very cautious individual, probably wise with his qualifications on a base with 2000 young men under his medical care. I was placed on a table and my right arm strapped down. They tried to anesthetize me with chloroform. I started to count down from one hundred as he poured the chloroform on the mask over my nose and mouth. At eighty I started to slur my words but recovered and continued down to sixty.

After three attempts to knock me out he lost confidence and became concerned he might knock me out for good. He put plan B into action. My hand was deadened and my other arm and legs were held down by my father and an assistant. Using a hacksaw he separated the hook in my hand from the body of the jigger. He then made a cut along my index finger near the tip of the hook. The initial opening was too short so he had to cut some more. The final incision was about 3/4” long. He was able to grab the tip through this opening and pull the hook out of my hand. Both scars are still obvious, sixty years later